Welcome back! Here is the follow-up to the Met Misc Rewind on the Bridge Cafe on Water Street.

An audio version of this post is in the works. If you are viewing this post as an email, you can click the title above to view the post with any current updates.

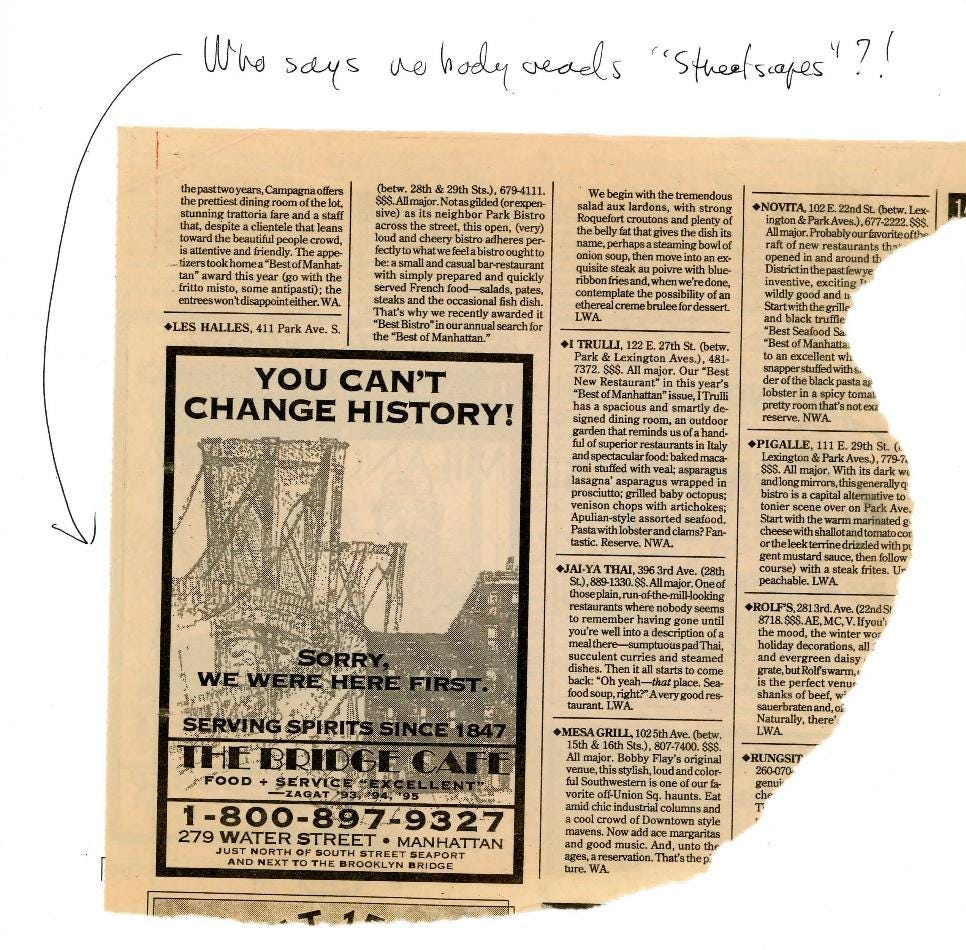

History can have a reputation for being boring and static, but I see it as a field with a constant stream of new developments: new resources becoming processed and digitized, new ways to rethink common narratives, forgotten people and lost documents to remember and recover. In my last post, Christopher Gray traced the work of “novice” researcher Richard McDermott as he unseated McSorley’s as the oldest saloon in New York City in favor of the Bridge Cafe. After the publication of the column, those at the Bridge Cafe were happy to brag about it, as you can see in the ad below.

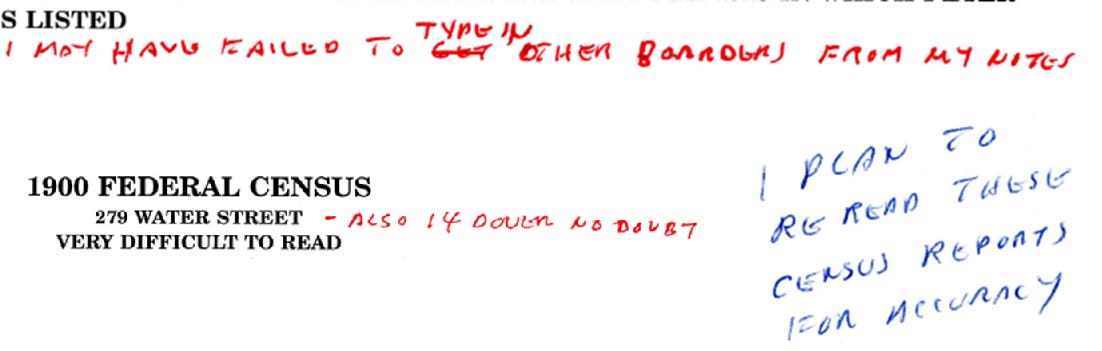

Perhaps I’m projecting, but the marginal notes throughout the material McDermott provided to Christopher show a level of somewhat neurotic “oh, I should double, triple check this” that I can identify with. Of course, this is important to do, until it gets in the way. (If anyone can give me the precise coordinates of that line, I’d love to have them.) These marginalia also call out the inherent fuzziness of some of this research. For example, old documents, especially handwritten ones, are not always perfectly legible. Also, a building's footprint can shift over time: the present-day 279 Water Street includes both the 1794 wooden structure on the corner and an 1827 brick building directly to its east on Dover Street, which were combined in the 1850s. It appears the address “14 Dover Street” was in the mix at some points; this address no longer exists today.

Christopher loved to dig into a bit of New York City apocrypha to test the truth of the matter. As the adage goes, the truth is stranger than fiction. I suppose I don’t know that it’s stranger for a bar on Water Street to be older than a bar on East 7th Street, but the pathway of the research drawn out in this article fascinates me. Both the diligence of the archival staff at Municipal Archives to double-check their records and the happenstance of seeing the saloon license on the wall at Fanelli’s were necessary for this tale to play out how it did.

Since 1977, the building at 279 Water Street has enjoyed landmark protections as part of the South Street Seaport Historic District, and thus had an entry in that district’s Landmark Preservation Commission designation report. (In short, the LPC provides local protection and regulation for historically significant buildings and districts.) The beginning of the entry on 279 Water Street reads “thought to have been constructed in 1801,” but it gives no further detail on the source for this.

Using directories and historical newspapers, Richard McDermott was able to date the building itself (not the saloon) back to 1794, when a “grocery and wine and porter bottler establishment” in the building was opened under the care of Newell Narine, who rented the building from James H. Kip (of the Kip’s Bay Kips). Unfortunately, some of the historical record is available as a result of bankruptcy proceedings involving Narine. By 1797, he was in the debtor’s prison in present-day City Hall Park, with the remains of his stock of groceries auctioned off and his schooner Charming Hester seized by the sheriff.

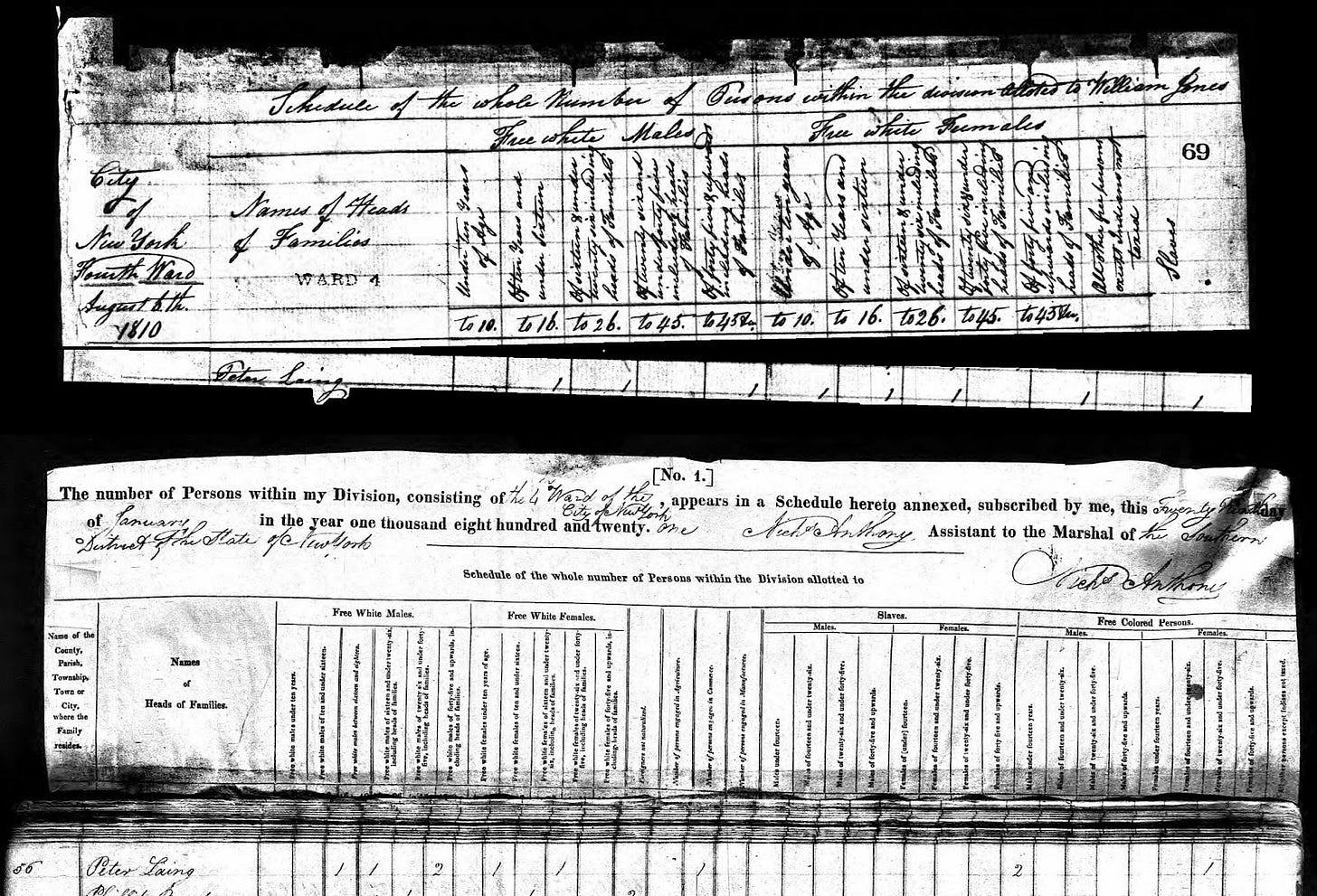

The LPC’s “Discover New York City Landmarks” map still shows the building’s construction date as 1801 and the owner/developer as Peter Loring, the latter likely being a mistranscription. In 1801, after the troubles of Newell Narine, Peter Laing began leasing the grocery store from James H. Kip, the same landlord, until he purchased the building in 1807. I do sometimes wish there were a mechanism for addenda in designation reports—or correction, in the extremely rare case that is a relevant issue—but perhaps that is a can of worms the LPC is not eager to open.

The 1810 federal census return for the Laing household shows one enslaved person, with no age or gender information. (There are no columns for “free colored persons” in the 1810 census.) The 1820 census shows two Black children under the age of 14 and one Black woman between the ages of 26 and 45, all with free status. These early census returns do not provide names beyond the heads of household. Slavery was not completely abolished in New York State until 1827, although the process of gradual emancipation began in 1799. The 1810 census is compelling evidence for 279 Water Street being one of the oldest surviving Manhattan buildings where an enslaved person once lived.

The way LPC designation reports are written has shifted over time. Compare the brevity of the entries in the 1977 South Street Seaport Historic District report to the much more specific entry on McSorley’s in the 2012 East Village/Lower East Side Historic District report, excerpted below:

Supporting the claim that McSorley’s Old Ale House first opened on this site in 1854, tax records reveal that the first improvement on this lot may have occurred in the mid-1850s. Though tax records note the lot as vacant until 1860-1861, the value of the lot increased steadily between 1848 and 1856, indicating that a small structure may have been constructed here and not recorded (note: nearby lots did not change in value during the same period). … Tax records confirm a two-story structure on the lot by 1861. By 1865, the property is valued at $11,000 and is noted as having a five-story structure. It is unclear whether the earlier two-story structure was altered into the present five-story building, or whether an entirely new building was constructed ca. 1865.

I appreciate this kind of writing that is very specific about sources and also acknowledges the uncertainty inherent to working on this type of research.

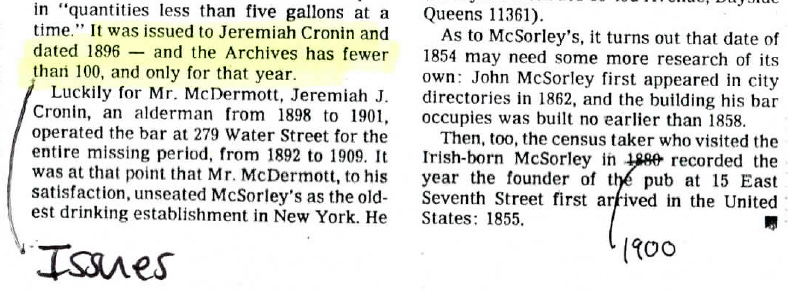

Of course, everybody’s work is subject to addenda and corrections. Some of my favorite writing of Christopher’s is from his corrections. In fact, he filed a small one with this article: the census entry recording McSorley’s immigration date was from 1900, not 1880.

A close reading of the original line about the liquor license also reveals further issues. The original line read, “It was issued to Jeremiah Cronin and dated 1896—and the Archives has fewer than 100, and only for that year.” The liquor license was actually issued to “Cronin & Murphy,” and the names Jeremiah J. Cronin and John C. Murphy are given on its verso. Also, the 1896 at the top of the license is actually part of its expiration date; it was issued on September 13, 1895. The collection of licenses is fully digitized now. Issuance dates range from 1895 to 1897, and there are over 4,000 licenses contained in this collection. Perhaps the “fewer than 100” and “only for [1896]” details cropped up before the collection was fully processed.

A familiar name appears in the collection’s finding aid: “In 1997, the licenses were catalogued by historian Richard McDermott, and rehoused.” McDermott has since passed away. Some issues of his quarterly New York Chronicle are available at the New-York Historical Society.

McSorley’s can still claim the title of oldest continuously operating saloon in New York City, as the Bridge Cafe was forced to close in 2012 after Hurricane Sandy. Most of the restaurant was flooded with over five feet of water. A February 2020 article in the Wall Street Journal details then-owner Adam Weprin’s efforts to repair and reopen the Bridge Cafe. One can assume the pandemic did not help the business. Weprin sold the building in 2021.

I anticipated this article would have a somewhat depressing ending, but some online perusing reveals that a new full-service liquor license for Bridge Cafe NYC LCC was conditionally approved by a community board on May 28, 2024 (see page 14 here). Perhaps there is still some hope for this institution to extend its story into the 21st century.

As you may have noticed, I have not posted in the past month. I have been caught up in the logistics of preparing for and recovering from top surgery. I look forward to making up for the fallow month with an increased posting schedule.

I am grateful to P. Gabrillet Foreman et al. for the community-sourced document “Writing about Slavery/Teaching About Slavery: This Might Help,” available online here.

Thank you to Dr. Jude Webre for his assistance with editing.

This post about corrections begets its own. A previous version read that McSorley’s could still claim the title of oldest “continually” operating saloon, when the more appropriate word is “continuously.” Thank you kindly to Andrew Alpern for pointing out the difference between how the two are typically used, along with the fact that the Bridge Cafe can claim the title of the oldest continually operating saloon in New York City.