An audio version of this post is pending my further recovery from this cough! It will be linked in this section once I am well enough to record and upload it. If you are viewing this post as an email, you can click the title above to view it with any current updates.

Historic landmaps are a great way to get a sense of how a New York City block has developed over the past two centuries. This post is the first of a series on research methods that will be a bit more technical in nature, but I hope you stick around even if learning about research methods is not your primary reason for reading this column. It is my personal opinion that it is extremely fun to go map mode! Let me elucidate with an example on the Upper West Side.

My most common use case for historic landmaps is parsing “addresses” from older building permits given in metes and bounds. That is, rather than giving a house number (e.g., 5-15 West 87th Street), the location of the buildings is given in terms of what side of the street they’re on and how far away they are from the nearest corner (e.g., West 87th Street, north side, 150 feet west of Central Park West). The original 2004 version of our New Building Permit Search database, which will eventually receive its own research methods article, provides the following (emphasis added):

Some permits are not rendered in address form, but in “metes and bounds”—that is, “86th, 175'e of Amsterdam” indicates the building lot beginning 175' east of the corner of West 86th Street and Amsterdam Avenue.” To interpret this, go to a library with a collection of landmaps of New York City (which give such measurements)—there are none on-line.

Much has changed for the intrepid researcher in the last two decades, including the digital availability of historic landmaps. From the New York Public Library to the David Rumsey Map Collection, to present-day tax maps from the Department of Finance or zoning and land use maps from the Department of City Planning, there is almost an overabundance of material to sift through. More on the technical aspects of that in my next research methods post.

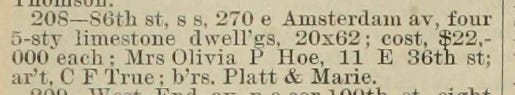

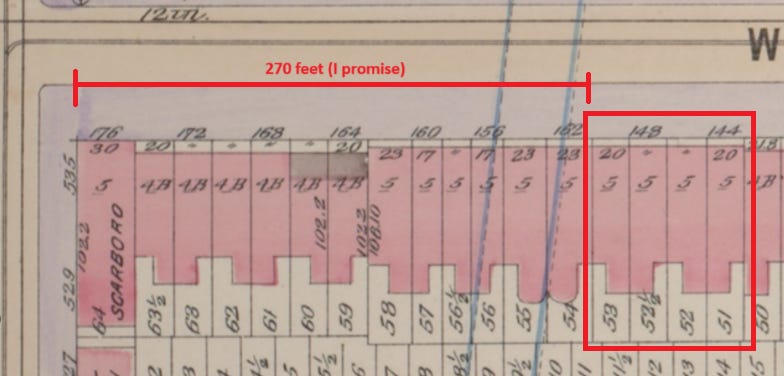

Let’s start with the “metes and bounds” issue presented in the quote above. The example given is just a hypothetical; here’s a real one from the same block from New Building permit 208 of 1894: “86th st, s s, 270 e Amsterdam av.” In English, this is on the south side (“s s”) of West 86th Street, 270 feet east of Amsterdam Avenue. This particular permit is for four five-story dwellings with frontages of 20 feet and depths of 62 feet.

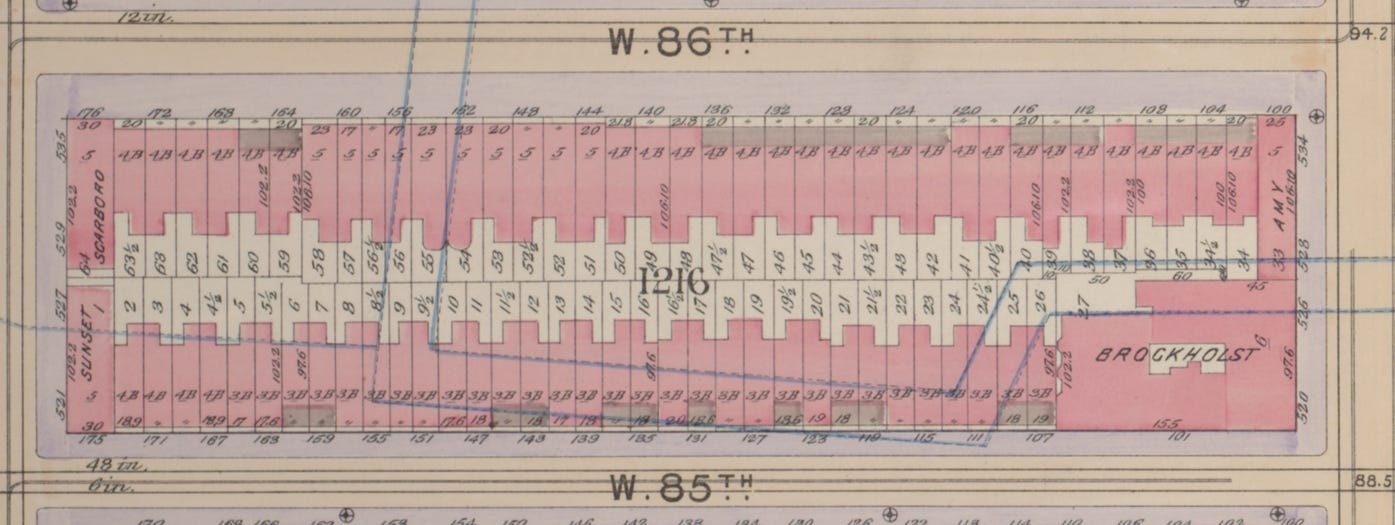

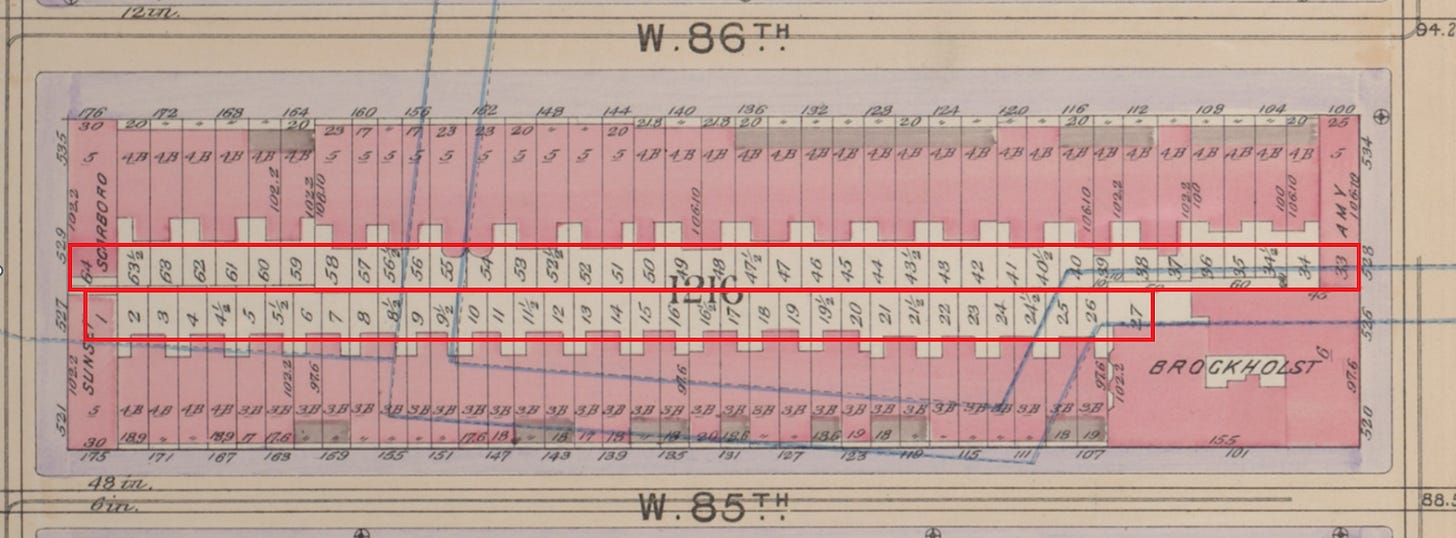

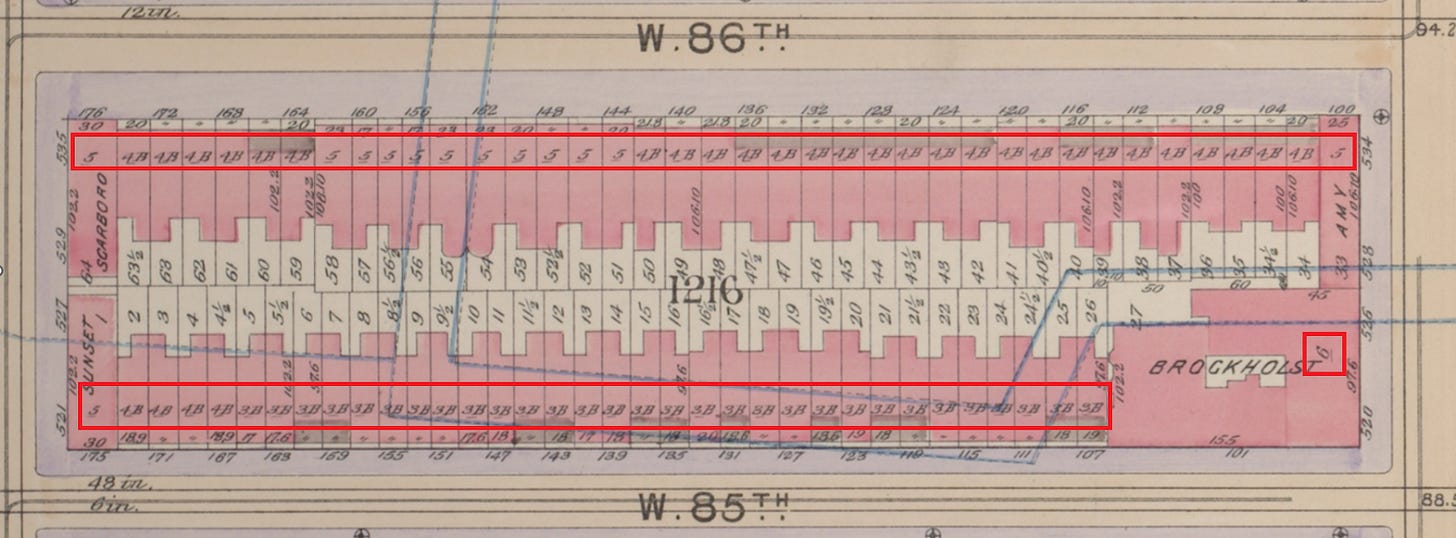

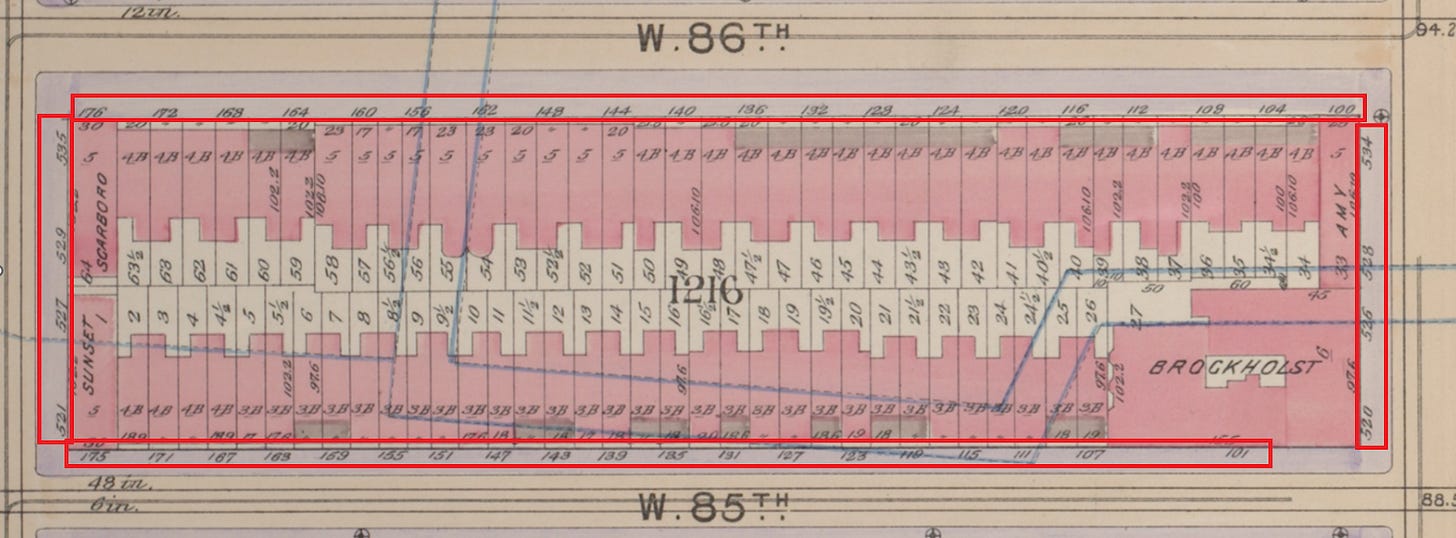

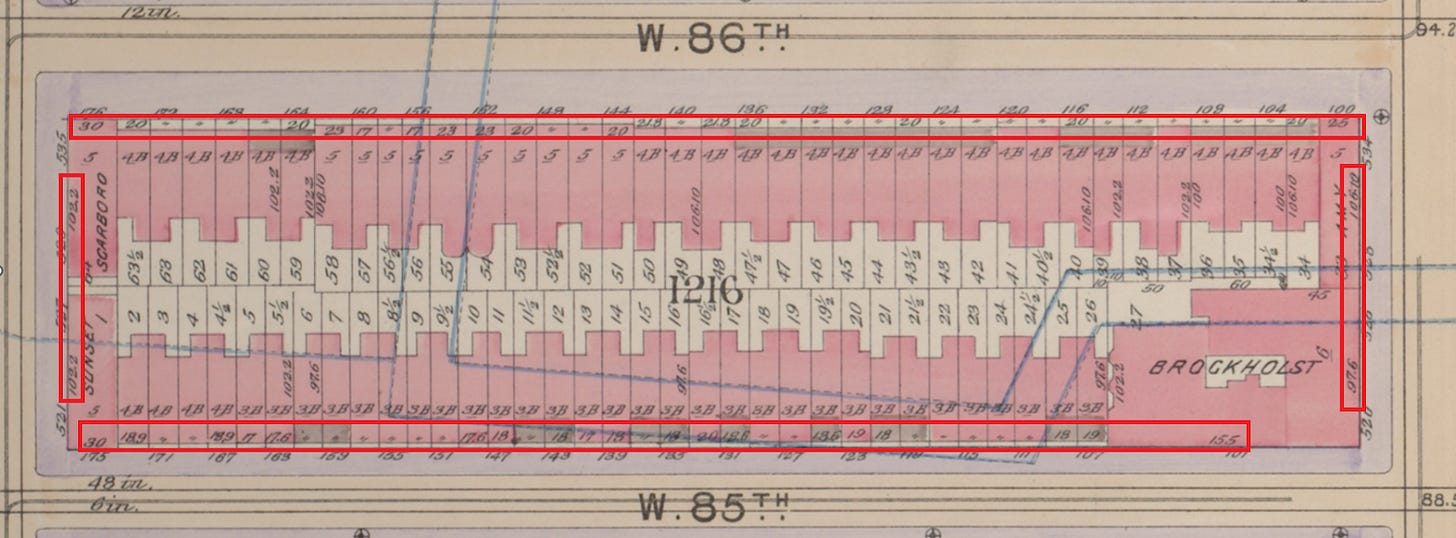

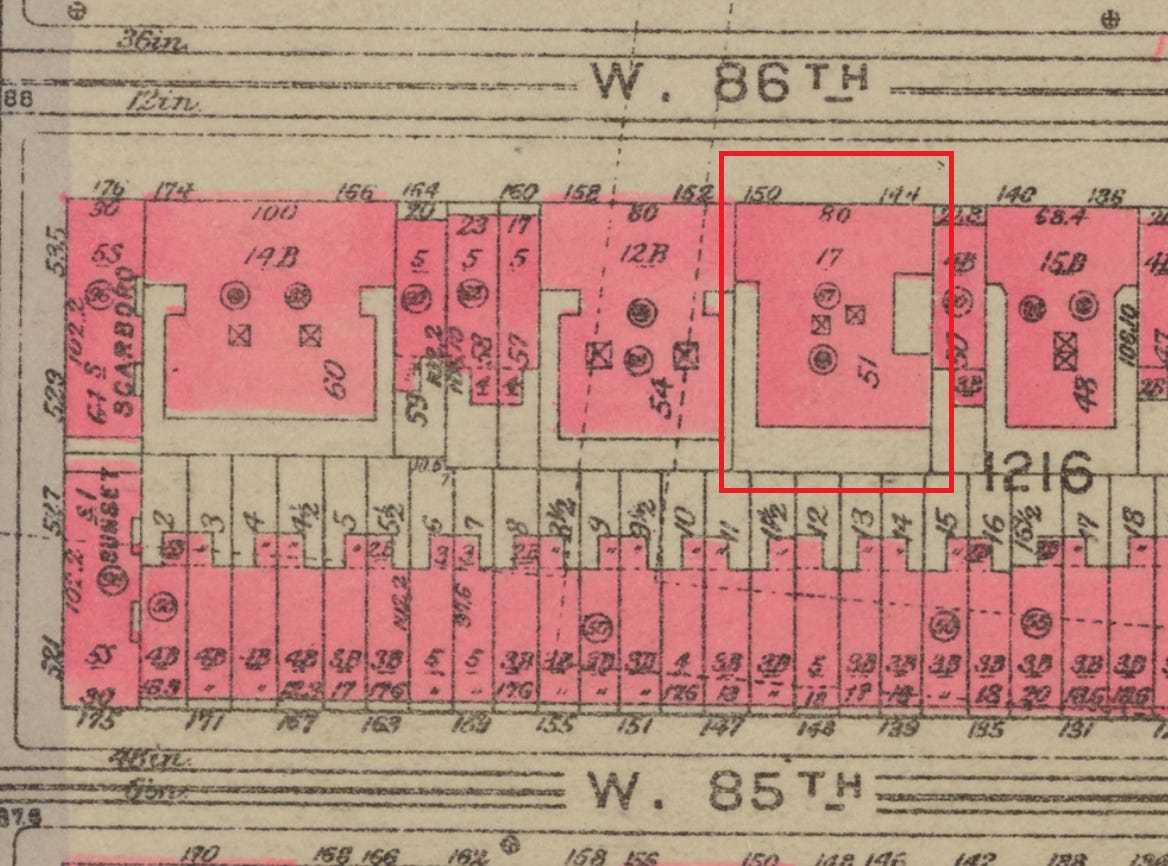

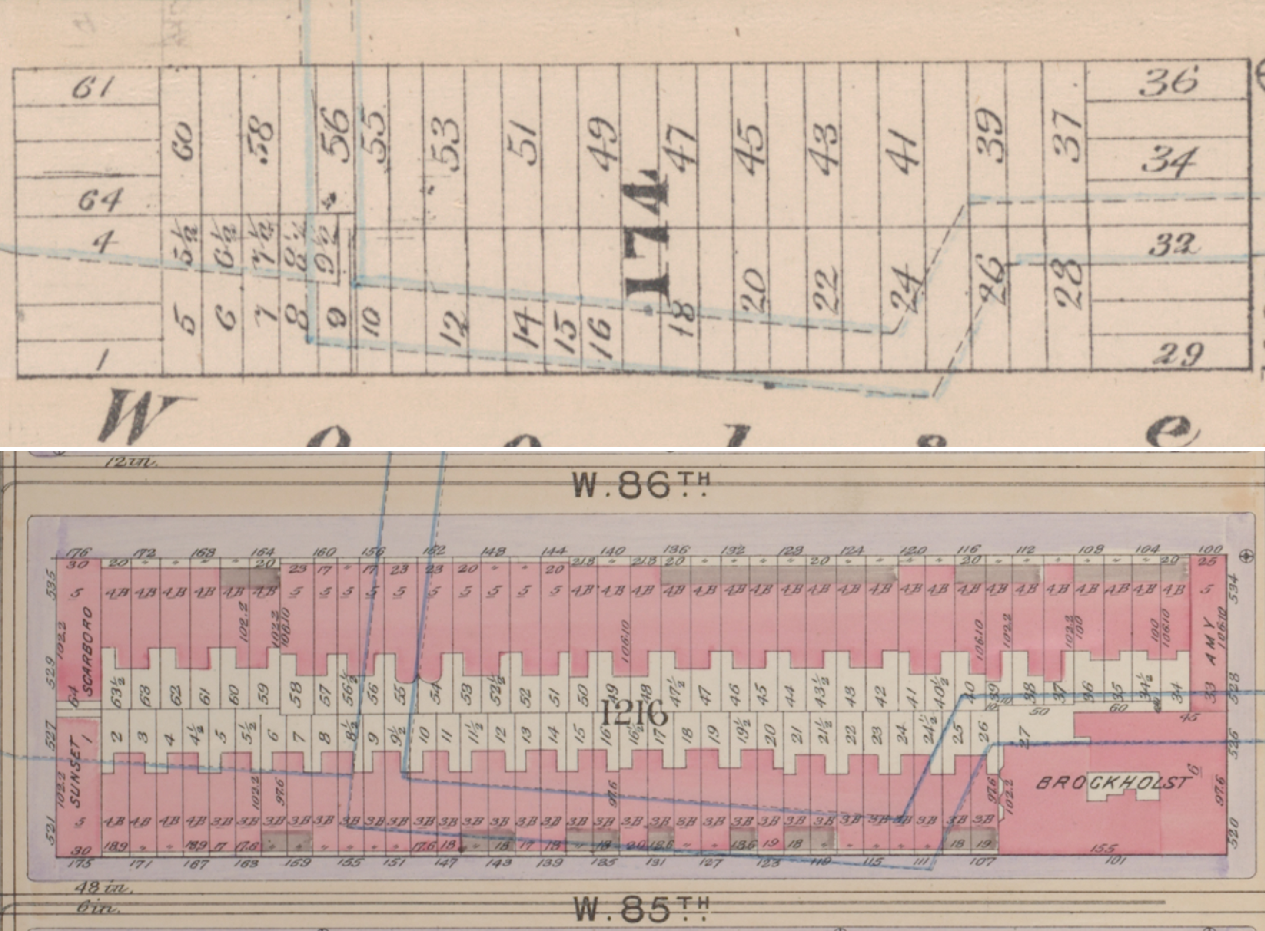

Below is an 1898 map of the block. West 85th Street and West 86th Street are visibly labeled on the bottom and top, respectively. Amsterdam Avenue is at the left, and Columbus Avenue is at the right of the block. If you would like to zoom in further, or view the larger context of the surrounding blocks, the full plate is linked in the caption below.

We can determine the house numbers of the four buildings designed under this permit from the map above. Let’s go over what the various numbers on the map mean.

Every block in Manhattan between Houston Street and West 155th Street was laid out in a grid system and numbered in the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. Each of these numbered blocks was split up into numbered lots, whose numbering changed as farmland was subdivided into smaller apportionments, which were often subsequently rearranged over the course of the following centuries.

On the block shown below (Block 1216, the large number in the center), you can see Lot 1 is at the southwest corner or lower left, Lot 2 is adjacent directly to its east, and so on. The lot numbers here are closer to the interior of the block, but this can vary from map to map. The easiest tell for how the lot numbers are being represented is that they are roughly in order and go around the block, typically starting at the southwest corner and moving in a counterclockwise direction. Here the lot numbers end at 64, at the building labeled as the Scarboro.

You might notice that for the Brockholst, the largest building on the block, there are some missing lot numbers! That is, the lot numbers skip from 27 to 33. This indicates to me that before the Brockholst was constructed, there were at least six lots that were then combined. This could mean that six or more empty lots were combined, or that six or more buildings were demolished for the Brockholst (less likely in this particular scenario). A loss of lot numbers (and block numbers, when superblocks are involved) is common as buildings with larger footprints are constructed over time. As you can imagine, this can complicate research, especially for demolished buildings with lots that no longer exist.

This block also includes some lot numbers with ½’s in them. Today, those are represented a little differently: the former Lot 4½ is now Lot 104, Lot 5½ is now Lot 105, Lot 21½ would be Lot 121, Lot 63½ would be Lot 163, etc. It can be a little confusing because these numbers are no longer technically in order, but I’m sure there are benefits to making everything whole numbers. Many of these “half-lots” have been lost over time, as smaller buildings have been replaced with buildings with larger footprints. The designation “half-lot” does not necessarily mean that these are half the size of a standard lot. Lots are often rearranged before anything is constructed on a block, as we will see later in this post, which can contribute to where the half-numbers are placed.

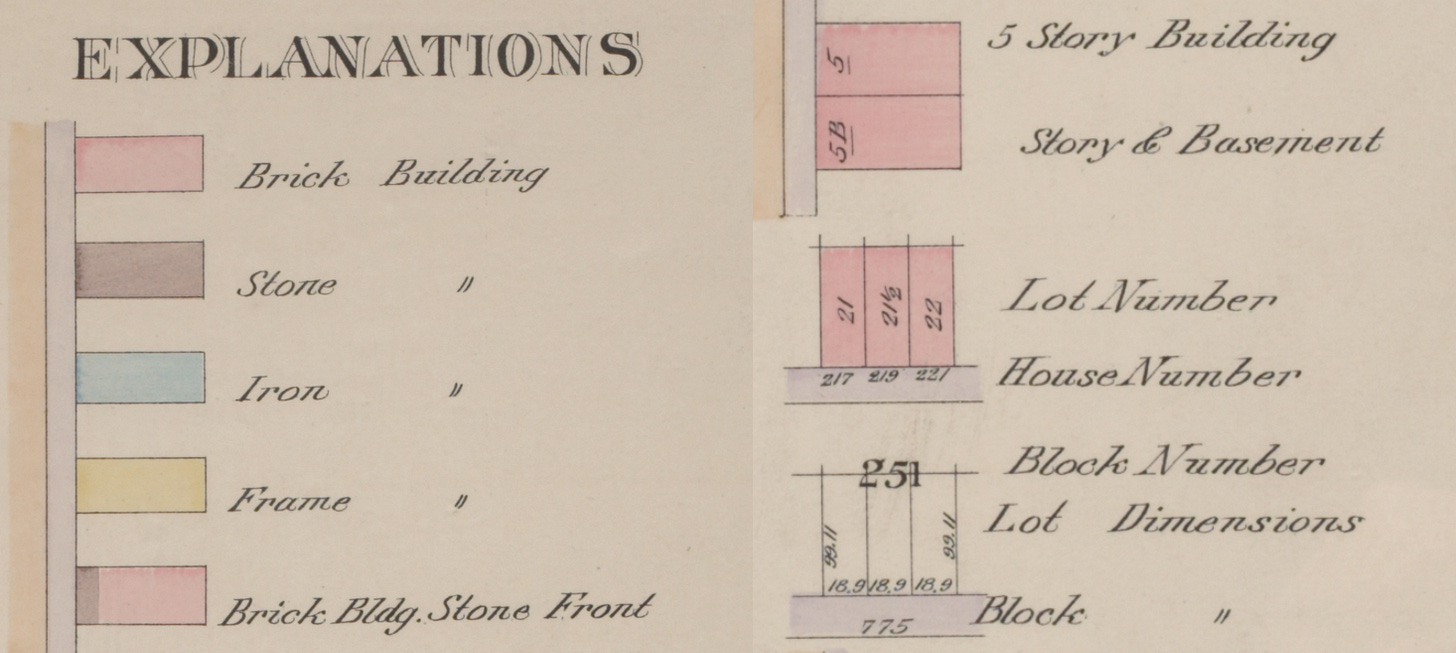

You can also glean some information about the materials of the buildings from the 1898 map: red represents brick and the brown/gray-ish color represents stone. In 1898, this block’s frontages are entirely filled by brick buildings, some with stone fronts. There are also a few building names included for apartment buildings here: the Scarboro, the Sunset, the Amy, and the Brockholst.

The small number with an underline on each building gives the height of the building in stories. “B” is used to designate a basement, or a story partly below curb level but with at least one-half of its height above curb level. (A cellar has more than one-half of its height below curb level.) On Block 1216, Lot 1 (the Sunset) is a five-story building, Lot 2 is a 4-story building with a basement, and so on. Similar to “B”, “S” is often used to show that a store is present. For example, “5BS” would indicate a five-story building with a basement and a storefront.

The numbers on the street side of the buildings indicate the addresses or house numbers on those streets. For example, Lot 1 is 521-527 Amsterdam Avenue and 175 West 85th Street.

The dimensions of the lot are also given, on the interior side of the building. Again, for Lot 1, the frontage is 30 feet on the West 85th Street side and “102.2,” which indicates 102 feet 2 inches, on the Amsterdam Avenue side.

A guide to this type of information is also generally included in a legend near the index or outline map at the beginning of a volume of historic landmaps. A partial legend is shown below, and you can view the complete legend at the link in the caption.

Okay! Now that we can parse most of the information available in this rich and dense document, let’s see if we can figure out the house numbers for the building permit I mentioned earlier. Again, the permit is for four five-story dwellings on the south side of West 86th Street, starting at a point 270 feet east of Amsterdam Avenue. Using your calculator of choice (I prefer the sum function in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet), you simply add up the lot dimensions until you get to 270. Or, you can just trust that I did the math correctly—I am a former mathlete! Luckily, the numbers add up to what we need them to, and there are four five-story buildings at 144-150 West 86th Street with 20-foot frontages exactly where we would expect them to be in 1898.

The buildings described as limestone here are shown as brick, which is within the range of typical variations you might see. Occasionally, the metes and bounds don’t add up quite correctly, or the buildings are not present at all! This can indicate that a new building permit was changed before it was carried out or perhaps abandoned completely. When working with metes and bounds, you also need to take into account the effect street widenings or similar changes can have. Another wrinkle: people in the late 19th century were not immune to human error, although this comes up fairly infrequently. (I will say the satisfaction of figuring out an 1880s typo is unmatched.) If what is present in a permit varies too widely from what appears on a landmap, I tend to start looking into other sources, such as the New Building docket books, to find a completion date or evidence that a plan was abandoned.

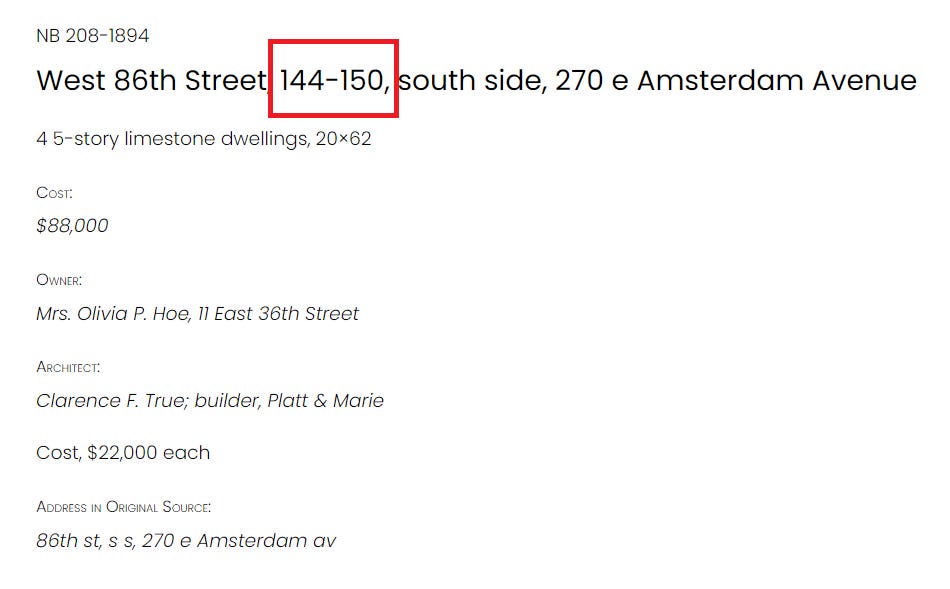

Whenever I develop information about house numbers for a permit given in metes in bounds, I include it in our office’s New Building permit database. So, the entry for the 1894 permit on West 86th Street appears as it is below, including the house numbers. Hopefully, this makes information easier to find and parse for anyone using the database to research their own building, the buildings that preceded these buildings, and any other kind of building you might be interested in.

Now, anyone who lives on this particular block might be wondering: what dwellings at 144-150 West 86th Street? This is because West 86th Street has been significant redeveloped since the turn of the 20th century, with many single-family dwellings being replaced by larger apartment buildings, including all of the houses built under this permit.

A 1930 map below shows the apartment building that stands on the site today. Since we now know how to read a landmap, we can infer that Lots 51 to 53 were combined into Lot 51, where a 17-story building stands at 144-150 West 86th Street. The 80-foot frontage of the larger building matches the former four 20-foot frontages of the row of 1894 dwellings. There are some other markings on the 1930 map that show the building is fireproof (i.e., it has steel construction), the main depth of the building is 87 feet, and the locations of the two elevator bays. The full explanation legend is available on the accompanying outline and index map plate here.

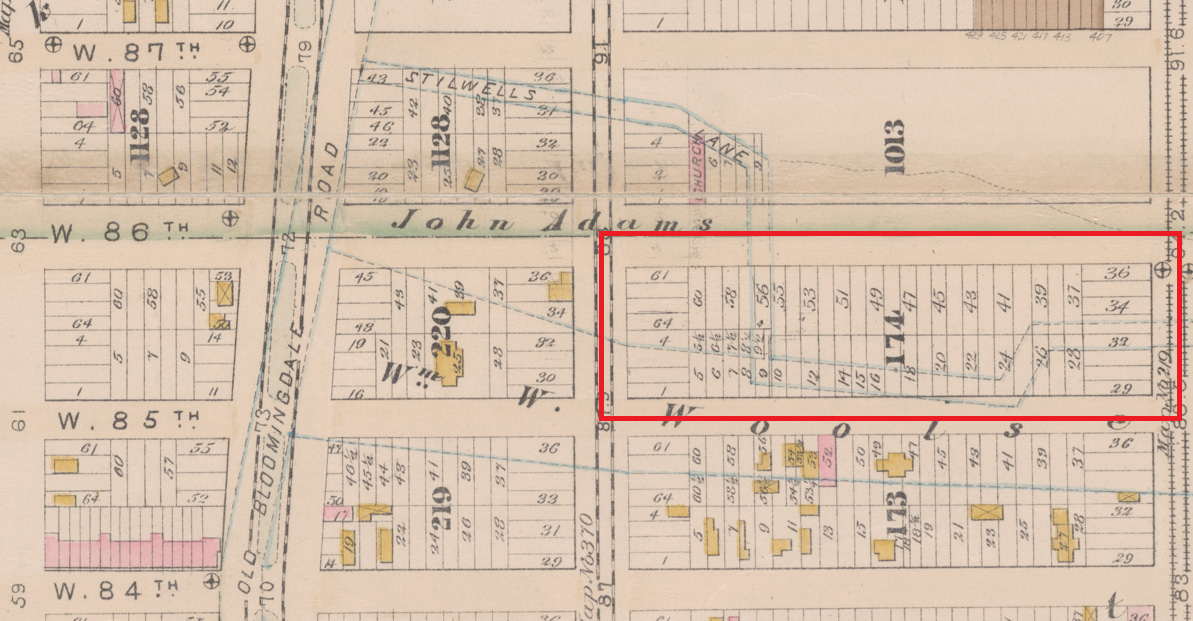

You may have also noticed some weird crooked blue lines in the background of the 1898 map, also shown as dotted lines in the 1930 map. According to the 1898 map legend, these represent “old farm lines.” If we go back in time a little more and take a look at the 1885 map shown below, when the neighborhood was only sparsely populated with mostly wooden frame structures (shown in yellow, as per the key included earlier in this post), we can see that these blue lines correspond to an old street: Stilwells Lane. I have highlighted present-day Block 1216 below, which is numbered as Block 174 on the 1885 map.

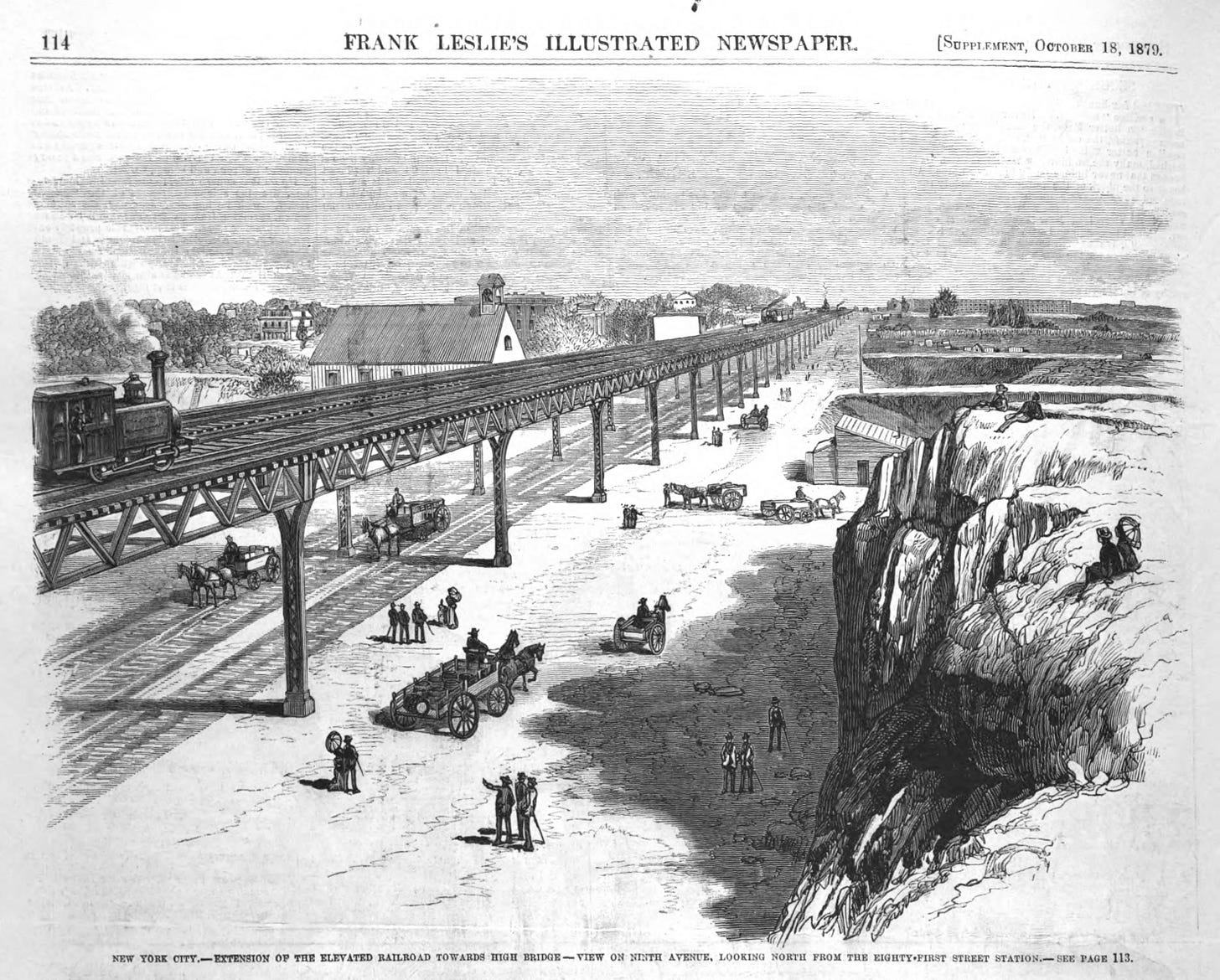

Images of this neighborhood in this time period are difficult to come by, but the wood cutting below shows Columbus Avenue (then Ninth Avenue) looking north from West 81st Street, just northwest of where the American Museum of Natural History is today. You can also see the elevated railway shown in the image below on the right edge of the map above as railroad tracks. Both images also show wooden frame structures alongside large tracts of empty land on still-developing streets and blocks.

No structures were present on present-day Block 1216 in 1885, but the outline of Stilwells Lane matches both the 1898 and 1930 maps. Interestingly, the lot shapes changed significantly between 1885 and 1898 during the first wave of development of the block, especially the half-lots in the southwest corner. You can examine the changes below, and in more detail at the full plates linked in the image caption.

Stilwells Lane was named after Samuel Stilwell (1763-1848), a merchant and land surveyor who owned 125 acres of farmland in the early 1800s in what is now the West 80s of the Upper West Side and Central Park. A portion of Stilwells (or Stilwell’s, or Stillwell’s) Lane also went by “Spring Street,” as it led to what is now called Tanner’s Spring in Central Park and former Seneca Village. More on Stilwell and his land holdings can be found in the archaeological investigations prepared by Hunter Research, Inc., for the Central Park Conservancy here and here. These are quite long and detailed documents, so I recommend using the Find function (Ctrl + F on Windows, Command + F on Mac) along with both “Stilwell” and “Stillwell” to find the pertinent information. Early 19th-century history often necessitates dealing with spelling variations, alas.

Hopefully this gives you some context on why you might want to look at various historic landmaps and how to read them. For my next research methods post, I’ll be getting into the more technical aspects of how to access maps on specific online platforms. I felt that this was dense enough that I didn’t need to layer the issue of street renumberings and renamings on top of it, but that will also be addressed in a later research methods post.

Until next week, when I’ll return with another “Met Misc Rewind” post with more of Christopher Gray’s writing from our archives!

Thank you to Dr. Jude Webre for editing assistance—and for the pun in this post’s subtitle.